Nyéléni 2025: A World of Food Sovereignty

By Sanuj Hathurusinghe

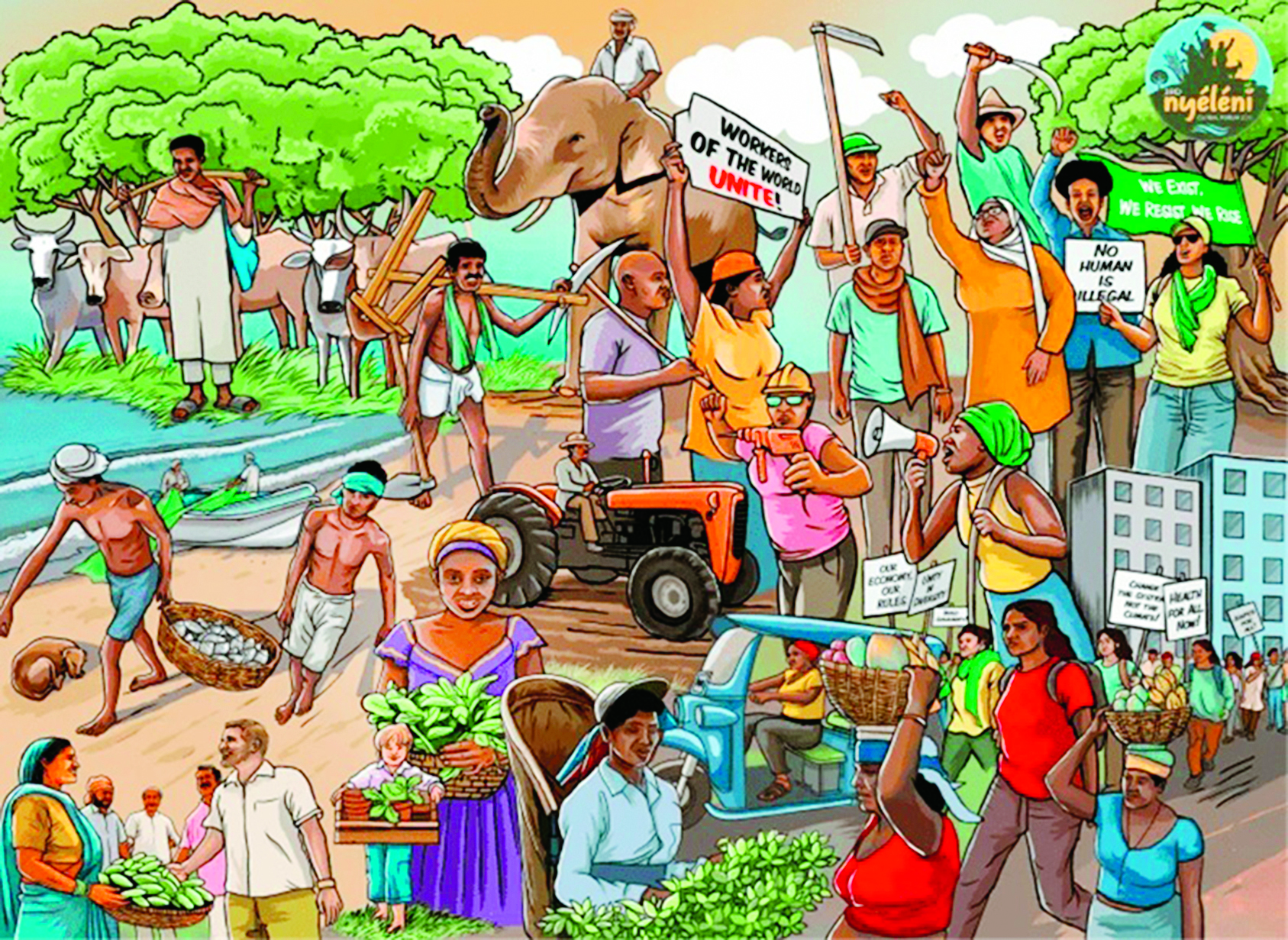

All preparations are made as Sri Lanka is poised to host the Third Nyéléni Global Forum, a pivotal event in the global food sovereignty movement. The Forum is scheduled to take place from 5 to 14 September 2025 at the National Institute of Cooperative Development (NICD), Polgolla, Kandy. The two previous editions of the Forum were held in Sélingué, Mali and this is the first time it is being held outside its country of origin. This edition is expected to bring together over 600 delegates from more than 120 countries, encompassing a wide array of stakeholders including small-scale food producers and Indigenous communities; fisherfolk and artisanal fishers; food chain and migrant workers; urban dwellers and hawkers; pastoralists and forest communities; womens movements and feminist groups; youth, students, academics, and trade unions; and climate justice and social economy organisations. The Forum is organised by International Planning Committee (IPC) for food sovereignty, Nyéléni Sri Lanka Steering Committee, Movement for Land and Agricultural Reform (MONLAR), National Fisheries Solidarity Movement (NAFSO), Lanka Organic Agriculture Movement, Centre for Environmental Justice (CEJ), Community Education Centre, Peoples’ Health Movement and Women’s Centre.

Hosting the Forum couldn’t have come at a better time for Sri Lanka as the country is also going through significant political, economic, and industrial change. Moreover, it is a great opportunity to let the layperson know about the importance of food sovereignty – as opposed to food security which is often talked about and paid much attention to – since it isn’t a topic or an ideology many seem to be familiar with. To know more about the upcoming Forum and the importance of the concept, ‘food sovereignty’ Ceylon Today contacted some of it’s organisers and stakeholders.

What is food sovereignty?

The origins of food sovereignty could be traced back to the 1996 World Food Summit organised by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). Although the Summit’s main focus was on food security; a concept that both challenged the corporate-dominated, market-driven model of globalised food production and distribution, a new paradigm to fight hunger and poverty by developing and strengthening local economies was also given birth to at the Summit. This wholesome and inclusive approach to sustainable food production which protects grassroot-level producers morphed into the concept of food sovereignty and it has captured the imagination of people all over the world including many Governments and multilateral institutions. It has also become a global rallying cry for those committed to social, environmental, economic and political justice. Following the World Food Summit, world leaders, organisations and civil society activists gathered again in Mali to discuss, plan and execute strategies to ensure food sovereignty. Accordingly, the first Nyéléni Global Forum on food sovereignty was held in Sélingué, Mali in 2007 while the second was held in 2015 at the same venue.

In a nutshell, food sovereignty is the right of peoples to healthy, culturally appropriate food produced sustainably, with an emphasis on local, community-controlled food and agriculture systems rather than corporate profit. It encompasses six key pillars: Food for People, Valuing Food Providers, Localising Food Systems, Placing Control Locally, Building Knowledge and Skills, and Working with Nature. This framework empowers farmers and consumers to make decisions about their food and agricultural systems, prioritising sustainability and local economies.

Evolution of food sovereignty and agroecology

Tracing back the origins of food sovereignty was Chairman of CEJ Hemantha Withanage. “Since the ‘60s when the ‘green revolution’ first emerged, food security has been often talked about. The green revolution focussed on ending world hunger, securing sufficient foods for communities and ending malnutrition. As a result, mass farming, hybrid variants of crops and agro chemicals were introduced to the agriculture industry. This however inadvertently took away conventional agriculture from the hands of ground-level farmers and handed it over to large-scale companies. Single crops were mass cultivated, forests were cleared, agrochemicals were widely used and as a result a lot of social and health issues emerged,” revealed Withanage.

These adverse effects didn’t go unnoticed. In 1969, scientists and economists realised the dangers of the trend and identified the limits of growth, especially in agriculture. Following the turn of the century, gene technology gained much traction and genetically modified variants took the centre stage replacing hybrid variants of the past. These technological advancements were again utilised to ensure food security but it also led to the big companies gaining monopoly over the agricultural industry as technology and research were involved in mass cultivation.

“A myriad of ecological issues have occurred due to mass agricultural practices. A forest is a treasure trove that benefits humans in countless ways. By clearing such a valuable forest for mass cultivation of a single crop isn’t ecologically viable. This was a huge issue in Brazil as the Amazon was cleared for mass cultivation of maize. In Sri Lanka too this has become a severe issue as mass cultivation has directly and indirectly resulted in the human-elephant conflict, deforestation, chronic kidney disease, cancer and other social issues,” Withanage furthered.

As a solution, ‘agroecology’ was introduced by the experts, which protects the environment, soil and the microbes living in the earth. This gradual transition also resulted in the talk of food security taking a broader and more inclusive approach – food sovereignty.

Not only does food sovereignty talk about ensuring food supply, it also focusses on the farmers’ right to seeds, to land, and to cultivate eco-friendly crops. It also sheds light on the land grabbing by companies, water pollution, and sustainable farming mechanisms. Going a step beyond just the production aspect of farming, food sovereignty encompasses the rights of indigenous and marginalised communities whose main livelihood is farming. It also involves small-scale fisher communities as well as women who directly and indirectly contribute to the food production.

An important event for small-scale farmers

“Small-scale farmers in Sri Lanka are facing a myriad of issues such as high production cost, lack of market access, severe dearth of resources, and depletion of natural resources. Farmers are also battling with land issues where they find it hard to secure lands for their farming activities, partly due to degradation but mostly due to other external factors such as infrastructure development, legal issues, and ownership issues. Moreover, the ever-increasing price of seeds has also become a severe issue. The seed market is almost completely controlled by the private sector with the exception of a few crops such as paddy. In paddy’s case, around 10 per cent of the seed market is controlled by Government agencies but still, the majority is controlled by the private sector. The human-wildlife conflict is also a rising issue,” commented Operations Manager of MONLAR Chinthaka Rajapakse when asked about the plight of the small-scale local farmer.

“When examining the trajectory of the agriculture industry in the country, some clear trends could be identified such as promoting export agriculture and commercial agriculture. While these trends aren’t necessarily bad for the future of the industry, it has been observed that an extra effort is placed to promote the technology aspect on agriculture such as innovative cultivating techniques and the infusion of drone technology into farming. Inculcating these technologies into the industry should be a gradual process in which the conventional farmer is allowed some time to make the necessary shift but at the moment, small-scale farmers are finding it difficult to adapt to these technologies which results in disadvantage for them. Another major issue is the debt burden the rural farmers face. Hill-country farmers as well as farmers of indigenous communities are in the habit of merging their habitats and farmlands together. In other words, they live where they farm and more than often, these lands are seasonal farmlands inside forest reserves.”

Looking at these realities, it becomes evident that industrial, export-oriented and commercial agriculture has aggravated the issues faced by small-scale farmers and rural farmers, rendering them victims of the process. The spread of agriculture demands large extents of land and this requirement is often fulfilled by merging existing farmlands together and/or acquiring residual forest lands for the purpose of agriculture. Small-scale farmers who operate on humble extents of lands often fall victim to these merges often influenced by big companies.

Elaborating further, Rajapakse mentioned how the conversion to renewable energy – the installation of floating solar panel farms – is affecting rural farmers and fisher folk. The inclusion of solar panel projects in reservoirs has created some indirect issues for the small-scale farmer with regards to obtaining water for their cultivation and proceeding with their aquaculture activities. Moreover, climate change – which perhaps is the biggest challenge the agriculture sector is facing world over – is affecting the small-scale farmer more adversely than mass-farming companies.

“Considering all these issues, it has become apparent that the grassroots farmer is continuing to face severe economical, agricultural and social issues. In terms of addressing these issues, the need of the hour is a discussion, an experience sharing, and a brainstorming in order to; ensure food sovereignty, secure the market, establish efficient and sustainable land management, manage seeds properly, conserve natural resources, withstand the adverse effects of climate change, introduce bearable loan/financial schemes, and so on. Above all, we need to build a community-based force of human capital which can tactically face these challenges.

Therefore, it is of great importance and significance that Sri Lanka hosts the Third Nyéléni Forum this year since the alternatives, collaborations, co-operative systems, community-based loan schemes, tactical approaches to withstand issues and experiences the forum would congregate could benefit the farmers of grassroots levels immensely, Rajapakse said.

Women empowerment

Commenting on the upcoming Third Nyéléni Global Forum, National Convenor of NAFSO Herman Kumara said, A systematic intervention which convenes all groups of small-scale food producers is much needed not just to find solutions but also to make their voices heard. This approach is also a vital component in ensuring food sovereignty. Within that the rights, knowledge, labour and importance of the traditional know-how of the labourers involved in small-scale food production are highlighted. More importantly, the often-neglected contributions of women are also discussed.”

Focussing on women empowerment, Project Manager-Women’s Centre Gayani Gomez said that the Third Nyéléni Global Forum could be an ideal platform for local women empowerment movements to gather momentum as well as make their voices heard.

“Food sovereignty doesn’t talk about just farmers, fishermen and indigenous people. It also talks about the labourer who contributes to the global supply chain. At the turn of the century the talk about a feminist economy gained traction but the topic was often regarded as a movement against men when in reality it was not anti-men but rather the unfair and conventional male dominance in various industries including food production,” Gomez said.

“Male dominance and new liberal economic ideologies often go hand in hand. New liberal economic strategies are formulated mainly to safeguard big companies which are coincidently run by a male-dominated management structure. In this system, the grassroots level economic and agriculture systems are often discouraged and disregarded. In the current economic system, the co-operative system finds it difficult to sustain itself. A small-scale grocer in a village is finding it hard to maintain a village shop as big corporations have expanded their network over rural areas as well. What used to be a wholesome social system in which benefits were dispersed among all aspects of society has now been turned into system which drives profits and benefits towards a selected few companies,” opined the Executive Director of FIAN Sri Lanka Thilak Kariyawasam.

Food security often involves financial strength. Not so long ago, a local politician famously claimed that cultivating is less financially viable than importing from India and hence, importing for cheaper price over cultivating at home was preferred. However, with Covid-19, many came to the realisation that having sound financial capability alone isn’t enough to ensure food security. Instances like the pandemic portrayed the importance of securing our seeds, our water resources, our sustainable cultivating practices, and the importance of having the liberty of cultivating what we want when we want, without depending on the mass-cultivated go-to crops which are forced upon people by the big companies. There is more than enough representation and resources allocated for big companies but little space and regard is given to grassroots level food producers. In this social reality, it is timely and important that Sri Lanka is hosting the Third Nyéléni Global Forum from which the country could gain a multitude of benefits.